Accents and writing different languages were recurring topics last week, in both my work and daily life.

Writing different languages

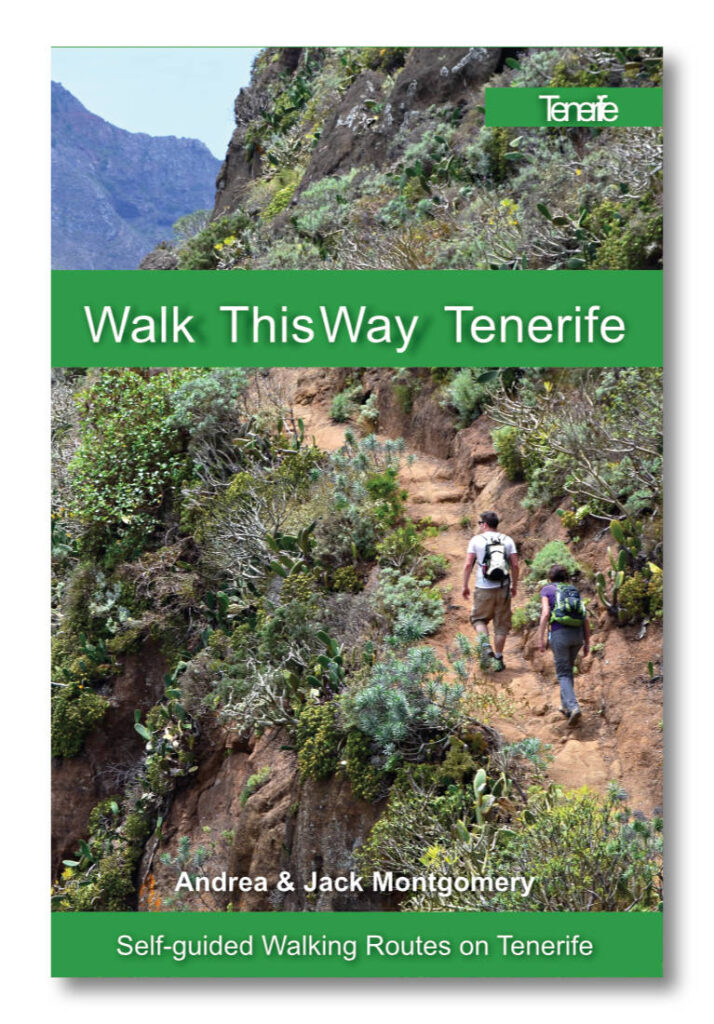

I use Spanish phrases throughout my Canary Islands novel. The balancing act when it comes to writing accents or other languages is in making dialogue believable and understandable. Whether I’ve managed to achieve that, I’ll discover soon enough as the novel is being checked by a beta reader.

A potential problem with using different languages or accents is there’s a danger of slipping into caricature, of straying into 1970s UK sitcom territory. I’m confident I’m familiar enough with Spanish to use it in the right context. I might not always be grammatically spot on, but if it feels natural and authentic, then objective achieved.

I face a different problem with another novel I’ve written. It features dialogue in modern Scots. I’m on relatively solid ground because that’s what I speak. It might have been toned down since I left Scotland, but it ramps back up whenever I pass the Fàilte gu Alba sign at Gretna Green.

Whether I’ve got it right isn’t the issue. The problem is how others react. Submitting a book whose characters speak Scots to London-based publishers who, in all likelihood, talk with RP accents, could be attempting to leap a cultural divide that’s too wide. I’ve submitted the first chapter to a writing competition judged by American authors. It’ll be interesting to see what they make of sentences like ‘Run faster ya useless bawbag, yer granny could leave you for deid.’

Accents in the real world

Recently, a person asked a young Ukrainian refugee whether she could understand me. I thought it was interesting, as the same question wasn’t posed about anyone else in the group (all English).

I had occasional problems being understood when I moved to Manchester in 1985. In one case, I asked a shop assistant for a packet of Benson & Hedges cigarettes, and she handed me a can of Coca Cola. At that time, I felt I was facing a form of anti-Scottish prejudice. But I was young and hadn’t travelled much, so I thought my experiences, and others like them, were unique to Britain.

The sister of a Basque neighbour on Tenerife had more trouble understanding Canarian Spanish than we did. I remember a Canarian TV presenter appearing on national Spanish TV, and they dubbed his voice. I’ve seen subtitles used when Canarians appeared on Spanish TV.

Living in a Spanish region, watching their TV, and being taught the language by people from different parts of the country made me realise, somewhat obviously when I thought about it, that every country has its own range of accents, some of which are not easily understood by people living in a different region.

As a young Scot, I may have bristled at people not understanding me, but then I don’t always understand people with a thick Glaswegian accent. During a stint of detached duty in Aberdeen with the Department of Employment, I hadn’t a clue what some of the locals lived in rural areas there were saying.

I also struggle with some English accents. I’ve had to ask people with strong West Country accents to repeat themselves on a few occasions since moving to the South West of England. Some English people don’t just struggle with non-English, English speakers, they don’t always understand their fellow countrypeople. Just look at Gerald in Clarkson’s Farm. His unintelligible dialect has made him a minor star.

Last week, I saw a Facebook post on about cold callers selling household goods around Somerset. What was interesting was how the people in the group referred to the hawkers in generic terms. They weren’t Scousers, Mancs, Geordies etc, they were simply northerners – by that they meant English northerners rather than from Scotland. Having lived in Greater Manchester for eighteen years, it struck me as illuminating and amusing. I could identify which specific part of England their fellow countrypeople came from better than the contributors to that Facebook group.

Getting back to the Ukrainian refugee who was asked whether she could understand me. I already knew the answer because I had learned something from living and working in different countries. When we are somewhere we don’t understand the language, all we hear around us are people speaking that country’s language. Unless someone is proficient in a specific language, they can’t differentiate between different accents. All that Ukrainian girl heard was me speaking English, just like everyone else in the group.

Experiences in different countries and various parts of Britain has fed my writing over the years. Those experiences also made me realise it’s not personal or prejudice whenever anyone asks me to repeat what I said.