Every so often someone tries to dazzle me with statistics. There are different ways to react when faced with stats. One is to blindly accept them, the other is to ask questions. Too many people do the former, one of the reasons it’s easy to hoodwink the masses.

Commissioning surveys, statistical analysis, and turning data into reports in plain English were aspects of my job when I worked for the DWP. I loved working with stats. Interpreting them is like deciphering code. But it involves more than simply reading numbers. It can often require reasonable knowledge of the subject matter. I’ve got a great example of this I’ll share in a bit.

What have statistics to do with writing?

The ability to not only read but understand statistics is an essential part of any writer’s toolbox. Stats are a fact of life for anyone who has a website, blog, or social media presence. And understanding stats is vital when carrying out research.

Once we can interpret statistical data it makes it harder for anyone to try to manipulate us. I see examples in the press and social media all the time of the way stats are used to mislead, either in the manner in which they are presented or in the ambiguous methodology used.

Misleading statistics

An example from a few years ago, just prior to the Brexit referendum, concerned poverty in the UK. A statistical table was used to show that Britain was the poor country of Europe, languishing just above Romania. The message was obviously about how better off the rest of Europe was. But what it didn’t make clear was the table referred to relative poverty, which relates to the standard of living compared to the economic standards within a specific country. Had it been absolute poverty – where individuals don’t have access to necessities like water, electricity, food etc. – then Britain was far higher up the table, and doing very nicely compared to most other EU countries. The skewed news report made readers believe Britain was ‘hard done to,’ helping manipulate them toward a pro-Brexit stance.

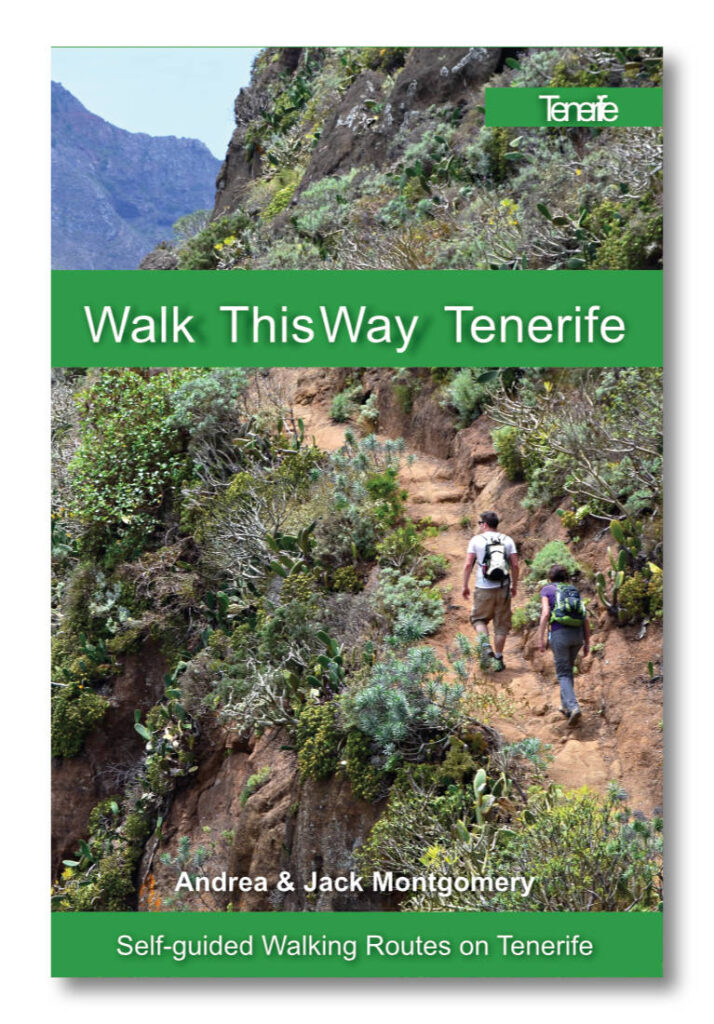

Statistics in travel writing

When we started our Real Tenerife brand in 2006, we knew the majority of visitors to Tenerife were interested in chilling out in a warm climate and nothing else, that there was only a small percentage of tourists who were seeking the authentic side to Tenerife. However, Tenerife and the Canary Islands welcome millions of visitors every year, so a small percentage was still a huge potential market. We knew what we wrote would be of little interest to many visitors to Tenerife, but that didn’t matter. It was liberating, we didn’t have to write to appease the masses. At that time, our calculations were based on rough data, now there are detailed stats to back them up.

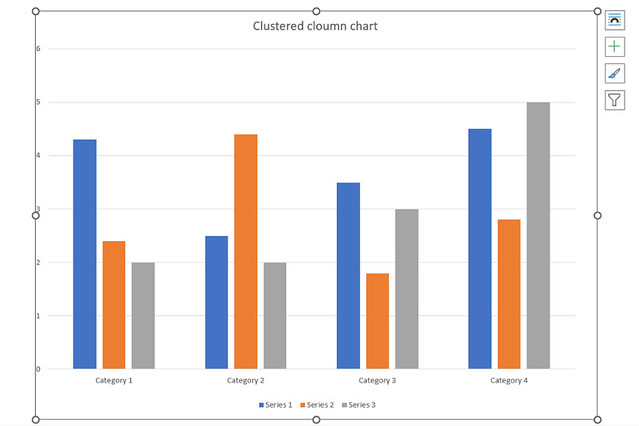

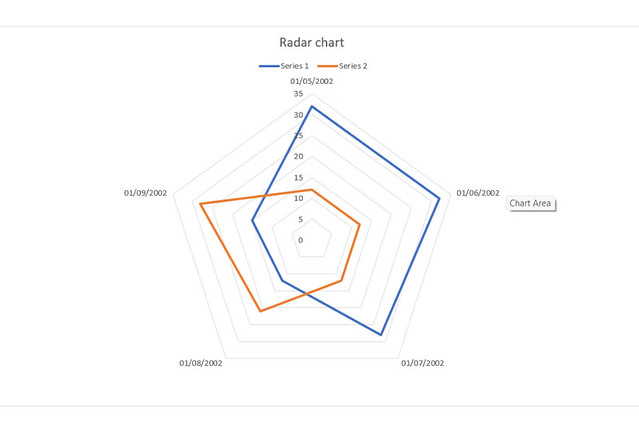

In 2019, there were just over 15 million visitors to the Canary Islands. Of those, 78% were there for the sunshine. Only 9.6% travelled to enjoy the walking; 23.2% for the gastronomy; and 20.3% seeking an authentic experience. But that makes close to 3.5 million visitors seeking the sort of things we write about.

This sort of analysis can be applied to other countries/activities on a greater scale to help identify potential market size. In terms of fiction writing, the stats mentioned previously tell me there’s potentially a decent market for the Canary Islands novel I’ve recently completed.

Why context is important

Back to the example from my days in the Civil Service. I was tasked with compiling a report about levels of unemployment among various minority ethnic groups in the North West of England. The one which experienced the lowest levels of unemployment was the British Chinese community, virtually no unemployment statistically speaking. However, part of my job also involved liaising directly with minority ethnic community organisations. While young British Chinese were mostly in employment, a significant amount worked in relatively low-level jobs in family businesses. Many weren’t successful in finding the jobs they were qualified for, but stats alone didn’t highlight this vital piece of information.

Five questions to ask to check the validity of statistics

- What’s the source?: If there’s no source referenced, move on. If there is a source referenced, what is it and is it reputable?

- Who was surveyed?: Out of a survey of one hundred people, 99% said they preferred one fast-food chain’s burgers to another’s. What if those one hundred people were surveyed as they left the burger joint they said they preferred? It’s important to know how those surveyed were chosen.

- How many people were surveyed?: The bigger the figure, the more weight the survey has, so long as those surveyed weren’t part of a targeted group (like the McDonald’s example).

- How are stats presented?: I’ve just read an article in The Guardian about Waitrose’s 2023 Cooking Report (4000 Waitrose shoppers surveyed) which stated one in seven people admitted to using takeaway food to feed friends when hosting a dinner party. You see this type of stat a lot. Turn the figures around and the reality is often the opposite of what the ‘headline’ is trying to suggest. In this case around 86% of people surveyed didn’t use takeaways when hosting a dinner party.

- What’s the bigger picture?: Context is everything. But this is more difficult to assess if we don’t have background knowledge (see the example above from my DWP days).

Statistics are wonderfully illuminating and informative. But numbers alone aren’t reliable without considering the questions above. Once we’re aware of that, it’s more difficult for anyone to try to pull the wool over our eyes by dazzling us with figures.