To begin writing, I have to get my head into the zone. It doesn’t matter whether it’s fiction or travel writing, I need to tune in the creative bits of my brain before I can start. And I can only do this in the morning. The trouble is that even trivial things can throw me off track. If we have to pop out to the nearest town just six minutes away, delaying the ‘writing’ by thirty minutes, then forget it. If something domestic has to be done (excluding prepping breakfast and cleaning up afterward) before I face the laptop, then there’s no point. There’s only one activity I can do before sitting down to write that helps fire up the creative numbskulls rather than dampen them down, and that’s walking. Walking and writing complement each other.

As everyone in Britain knows, rain has been a constant companion over the last six months or so. Here in Somerset, persistent rainfall leads to flooding and road closures. We’re fortunate. Our village sits in quite a lofty position for a county whose ‘Levels’ are one of the flattest areas in the UK. Somerset is known as the ‘land of the summer people’ because some parts were only accessible during drier months. Whenever we drop to a lower level, we run the risk of encountering road closures. But the sun has also shone most days. When it appears, we often grasp the opportunity to get out, to walk, even, heaven forbid, if it’s in the morning.

Topping up the bird feeder one morning last week, the sun planted a big warm kiss on my face. It was so pleasant, a true spring morning, that I suggested we go straight out for a 5km circuit of the surrounding countryside. It’s well-known walking is good for both mental and physical health. It de-clutters the mind and is a wonderfully sensory experience – the heady scent of spring blossom; birds cheering the changing seasons with their sweet song; the sight of a herd of wary red deer on the hillside; and the cool, cleansing sensation as we walk through a shallow stream of spring water, overflowing from its usual course to impinge on the lanes. The only sense not treated on our route is taste, but the freshness of the countryside is so intense, it feels as though it flavours the inside of my mouth. By the time we complete the circuit, climbing a steep narrow lane a neighbour told me was haunted to return to the house, I’m chomping at the bit to get in front of my keyboard.

Writing and walking routes

This is hardly a revelation. We encounter links between writing and walking all the time. Not far from us is the Coleridge way. The romantic poet who penned The Rime of the Ancient Mariner spent much of his time wandering the hills and moors of Somerset and Devon. At Lynmouth, where the Coleridge Way ends (or starts) there is a dedicated Poets Walk, connecting the Valley of Rocks with Lynmouth, which commemorates famous poets who walked there – Coleridge, Wordsworth, Shelley. What’s nice about that one is the public were encouraged to contribute, and now people’s poems add interest to an already compelling trail – There was a young man from the Valley of Rocks, who went around picking everyone’s locks… (that’s one of the examples, not mine).

Literary links to walking routes have turned up in various countries when we’ve put together Slow Travel holidays. In Drôme Provençale, we started an itinerant route from the town of Grignan, where some buildings are adorned with huge quills. Our onward journey took us along a Route des Poètes to cross Les Crevasses de Chantemerle, vertical cliffs above woods known for truffles and wild boar. The inspirational scenery from Les Crevasses reveals why it was favoured by poets.

In the Algarve, we mapped out a circuit from the arty village of Barão de São João which incorporated the Paseo dos Poetas, where extracts from poems are carved onto standing stones and boulders.

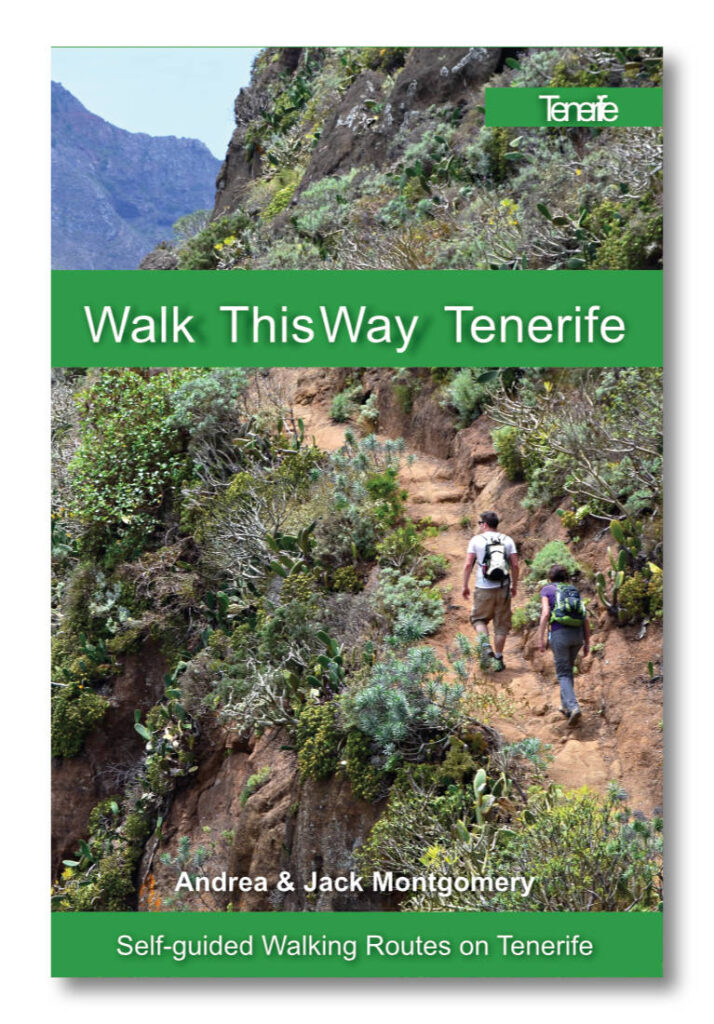

Then there are the times when there’s no ‘themed’ route, we’ve merely followed in the footsteps of other writers. Whenever we sweated our way through the foothills of Mount Teide on Tenerife, I often thought of Isabel Lady Burton, wife of explorer Sir Richard Burton, whose writing was wittier than her husband’s. She documented her ascent of Tenerife’s volcano in her book The Romance of Isabel Lady Burton, describing how she cast off her clothes as she climbed the mountain: ‘First I threw away my pike, then my outer coat, and gradually peeled, like the circus dancers do, who represent the seasons, army and navy, etc., until I absolutely arrived at the necessary blouse and petticoat.’

A Victorian lady in what was basically her underwear must have presented quite a sight to the muleteers who guided her and her husband.

In some ways, hoofing it around the countryside might seem at the opposite end of the activity spectrum from sitting behind a desk, typing. And yet it can be an integral part of the writing process. Simply put, walking unlocks creativity.