Many people have incredible travel experiences. Something like five and a half million Brits live outside the UK. Five and a half million! And that’s only the number currently living in another country. There’s a hell of a lot more who have done it and now reside back in Blighty. Andy and I are two of them. What makes our experiences any more interesting than that of the next person?

Imposter syndrome is something many writers suffer from. That confidence-devouring little imp spends a lot of time on my shoulder sniping things like – ‘What makes you think anyone is interested in reading anything you’ve written?’ Twenty years of writing for various outlets doesn’t quieten its whining voice.

A conversation Andy and I had last week prompted this post. It started with memories of a fearless fourteen-year-old girl jumping off a volcanic perch into a rock pool and ended with talking about our relationship with the finance minister of a Spanish political party. There is a link, but it’s a convoluted tale involving a mass water pistol battle during a fiesta where a virgin is paraded on a boat; a dodgy mayor who shopped at the same supermarket as us and, according to a friend who knew him since he was a boy, bribed locals with empanadas (pies); and our accountant who, for a period, was the local finance minister of a Spanish political party when they briefly held power in the town where we lived.

One small story that involved the consequences of a volcanic eruption, fiestas, localised Spanish politics, and the contents of the mayor’s shopping basket (mostly cat food). When we spoke about it, it careened off in numerous directions, awakening all sorts of absurd memories. Maybe that’s the norm. Travel and living in another country throws up bizarre experiences and characters.

The book that changed travel memoirs

Unlike many of the travel memoirs preceding it, Peter Mayle’s A Year in Provence wasn’t highbrow. It was an enjoyable and accessible account of what living in another country was like … could be like. It painted a beguiling picture that had people dreaming of living such a life – being introduced to food they didn’t know, strolling idyllic landscapes, negotiating the up and down challenges of dealing with a different culture, notching up quirky experiences, and encountering a cast of colourful characters.

But that was in a book. Real life isn’t quite like that. Except, sometimes it is.

Essential ingredients in a travel memoir

AI is a useful tool for writers, and I don’t mean as a replacement for creativity. It saves me masses of time on mundane tasks, time I can divert to writing. For example, while suffering from an attack of imposter syndrome, I asked it to list key ingredients any decent travel memoir should have, just to check I could meet the criteria. This is what it came up with:

- Locations should be interesting, with descriptions including sensory details to transport readers.

- It should include anecdotal stories to illustrate experiences and add colour to the narrative.

- Memoirs should focus on personal evolution changes the writer experiences.

- It should reveal what draws the writer to the destination and what do they expect to find there.

- The writer’s journey should challenge their assumptions, broaden their perspective, and lead to personal growth.

Overall, it’s pretty fundamental, but it does act as a rough check list. I use a similar process for fiction as well, checking my manuscripts conform to established structure for the genres they cover (mixed in both cases).

Personal Credentials

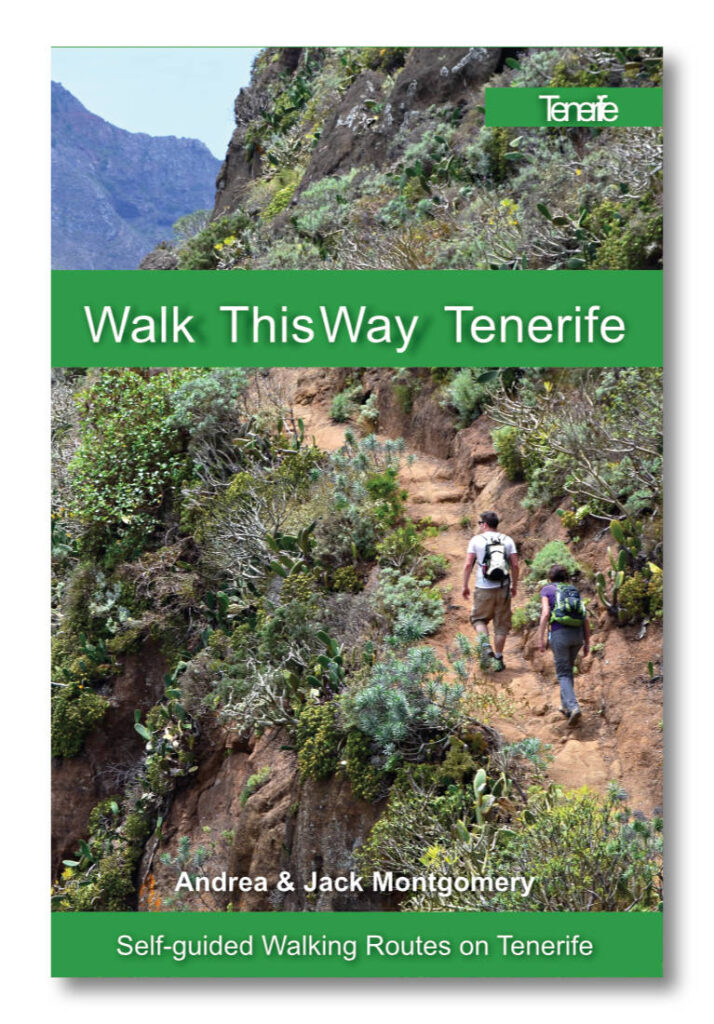

On Tenerife, we lived in a former animal shed in a banana plantation in a valley overlooked by Spain’s highest mountain. Neighbours included a man who hinted he was a spy; a woman who claimed she remembered her family fleeing Morocco in a car chased by armed men on horseback; and a young Basque man called Jesús who practiced hands-on healing.

We began our time in Portugal in an old farmhouse beside a smugglers’ trail on the border with Spain in remote Alentejo, before moving to a converted wine press in a small sheep farm beside a cork forest near the Sado Estuary. The farm was owned by a tiny Portuguese woman who spoke no English and who treated her sheep more like pets than livestock. Her friend, neighbour, and sometime handyman Señor Zé was equally diminutive and deaf. He never switched on his hearing aid, so shouted all the time. He hunted wild boar even though he didn’t like the taste of them.

All three locations involved environments that were alien to us, and which created a foundation for quirky experiences. Our job involved travelling around the places we lived (and way beyond) researching for travel articles – interviewing chefs, politicians, hotel owners, artisans, musicians, etc. while also walking across off-the-beaten-track areas, creating immersive Slow Travel holidays and writing guides about them. In circumstances such as these, a wealth of local knowledge and experiences rapidly builds up.

Whether this adds up to something other people are interested in is another matter. In the end, Andy and I are just two ordinary people who stepped off the corporate ladder to move abroad without a real clue as to what that involved. However, many of the people we’ve encountered along our journey have been extraordinary. For me, it’s the cast of characters that can make a travel memoir more enjoyable, interesting and, maybe most important of all, unique. That’s what Peter Mayle realised thirty-five years ago.