Places inspire us. That inspiration forms the basis of travel writing, or it did when writers such as William Dalrymple had me vicariously following him on his quest to find Xanadu, or when H.V. Morton made me laugh aloud at the idiosyncrasies of the Irish in his insightful book In Search of Ireland. Now, too much travel writing feels like little more than thinly disguised marketing rather than the consequences of curious exploration. That’s just the nature of today’s beast. But good travel writing is still inspired by places. Places, experiences, and people.

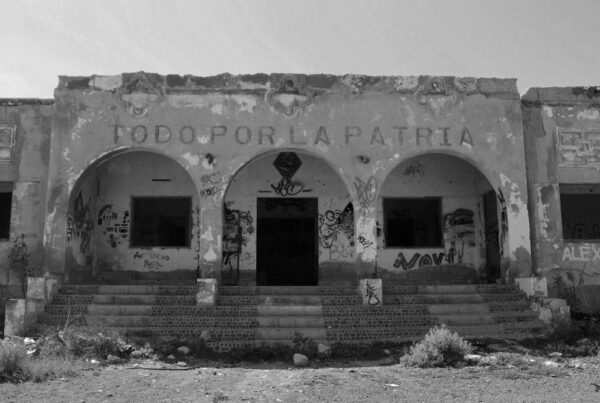

Whenever I write fiction, I find the same ingredients act as fuel for the imagination. My novel By the Time Dawn Breaks is fiction, but its inspiration came from strange tales and myths picked up travelling around the Canary Islands.

Travelling to the Isle of Bute for Christmas with my mum and sister, problems with the weather and a broken-down ferry forced us to take a different route than normal. Instead of jumping on the ferry from the mainland at Wemyss Bay, we caught a ferry from Gourock to Dunoon – a short voyage which transported us from the industrial West of Scotland into the Highlands. From Dunoon, we negotiated a single-track road that scythed through dense forest and across bleak hills, skirting the head of Loch Striven before descending to Loch Ruel to follow the coast to the small roll-on/roll-off ferry at Colintraive. It’s only 400m from the mainland to Rhubodach in the north of Bute; a five-minute crossing to swap the mainland for an island. Sounding like the start of a story written by Snoopy, it was a dark and foggy night as we crossed from Dunoon to Colintraive to emerge from the swirling mist at the tiny ferry port. The only lights on the other side of the water were the ones illuminating the jetty. Even though I grew up on Bute, it felt like we were heading somewhere remote, somewhere mysterious, somewhere different. It felt like we were characters at the start of a story.

Bute does this to me, it lights a fire under my imagination. Gliding across the water, watching the island grow closer, there’s a sense of travelling back in time. I don’t get this feeling going back to Stockport. Maybe it only happens with small places. I’m sure it’s intensified because Bute is an island, a 15-mile-long piece of land enclosed by a liquid fence. Its boundaries are real.

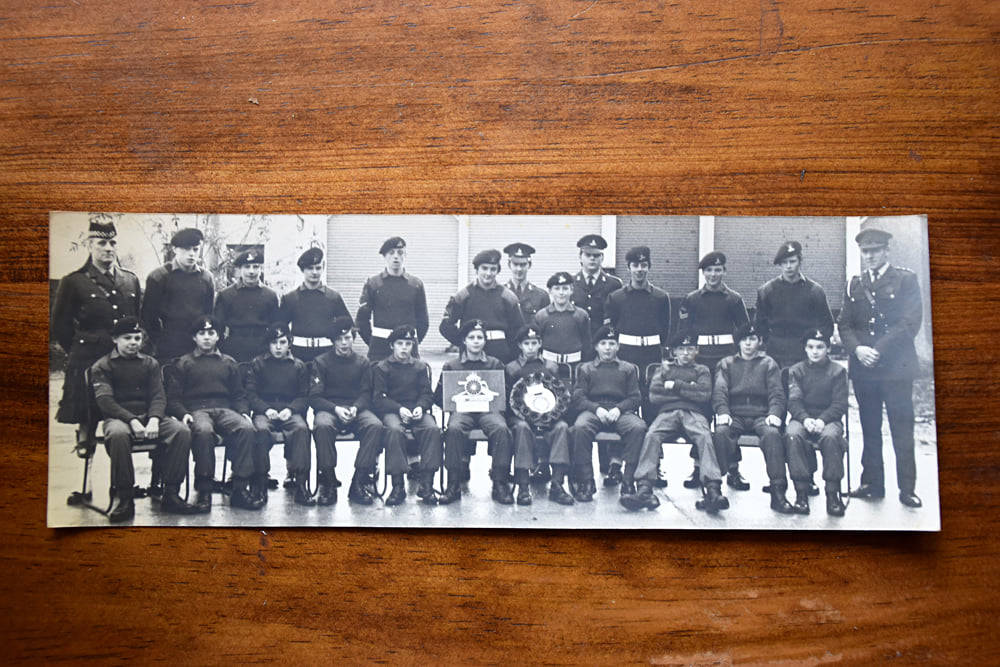

Each visit sparks potential ideas, sometimes linked to the past, sometimes triggered by the present. This trip was no different. The source was surprising, unexpected. It came from a chance meeting in a pub with someone I hadn’t spoken to in over forty years, Shamus, a bear of a man who seems a lot bigger now than when we were younger. I don’t mean overweight, I mean mountainous, with shovels for hands that swallowed mine when we shook. Apart from inhabiting the same island, my main connection with him was we were in the Army Cadets at the same time. I was there only because my dad was one of the two officers in charge. The other being a police sergeant of the sort you normally only find in Sunday evening TV shows, a softly spoken Highlander. I went under sufferance, feeling out of place because a) my father was one of the men in charge, and b) none of the other cadets were in my class at school. They were all strangers to me, but not necessarily to each other. That might sound odd in a small town, but there were distinct areas we tended to stick to when we were young – the Goy, the Bush, the middle bit where I lived. I felt an awkward outsider and didn’t want to be there, initially.

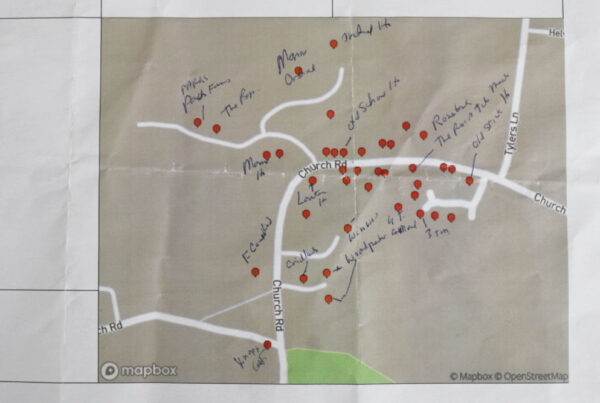

Shamus told me something I hadn’t heard before. He, along with some others, only joined the Cadets after being caught getting up to ‘mischief’ by the sergeant from the Highlands. He gave them a choice. They could either go to the Cadets or he’d inform their mothers what they’d been up to. Rather than risk the wrath of their parents, they trotted along to the Cadets as advised … and stayed. Not only did they stay, most also thrived and grew to love it. In the pub, we talked about some of the wild adventures we’d had, and how special it was. Not for the first time, I heard how transformative the experience had been. Thanks to the positive side of social media, I have been able to keep in touch with some of my fellow cadets, in recent years learning about things I didn’t know at the time, perceptions I had no idea about. It’s amazing how many lives were changed by the Army Cadets. For some, it did something school had failed spectacularly at. It instilled a pride that hadn’t existed before. Young men who were sneered at by academia could find their way around the countryside using a map and a compass, disassemble a gun and put it back together, and work effectively as part of a team. The idea that some young lives were transformed because of a friendly police officer makes you think. It is a story that virtually writes itself.

Hearing Shamus and others enthuse about memories of the Army Cadets made me re-evaluate my own experiences. Learning how to read a map at fourteen, I could never have imagined how essential a skill that would prove in later life for creating walking routes around Europe. In terms of character building, it was hard to surpass. I had to prove myself to be accepted by fellow cadets who didn’t view me as one of them. There were some I didn’t initially get on with who became close friends, an early and valuable lesson about judging people. Something Shamus said when I introduced him to Andy revealed another thing I didn’t know at the time.

‘Hmph,’ he remarked, eyebrows raised in surprise. ‘Your wife? I always thought you were gay.’

As Rabbie Burns poetically put it, ‘O wad some Power the giftie gie us, to see oursels as ithers see us!’