How do you fancy a plate of roast paw followed by tuna from the iron? These were two of the options I was presented with on an English menu on the Canary Island of La Gomera. One was tuna cooked on a hot plate – a plancha in Spanish, which translates into English as an iron. The other was pata asada. Pata means paw, but it’s also a female duck. On another occasion, Andy’s tastebuds tingled at the prospect of fish pie, only to be disappointed when she was presented with a cold and wobbly fish terrine. One glance at the Spanish menu and she’d have seen it was pastel de pescado, nothing like the fish pie listed on the English version. These, and mistranslations like them, are the reasons we always ask for menus in Spanish whenever we’re dining out in Spain.

Bad translations

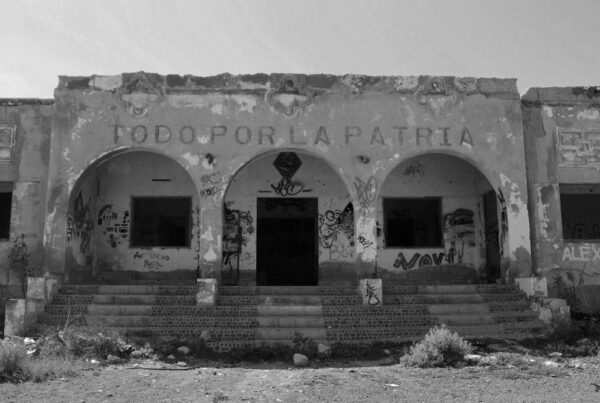

To be able to translate accurately involves much more than cutting and pasting a block of text into Google translate. That’ll help as a guideline, but it’s also the reason you’ll find ‘mistakes’ in travel articles where the writer has Google translated some of their information from a source that’s in another language. I’ve seen one UK travel site describe hiking beside rivers in Teide National Park on Tenerife, the author not realising the rivers were lava ones rather than water. A German newspaper was taken to task some years ago for reporting forest fires had reached the outskirts of the town of La Orotava on Tenerife. They had misinterpreted a Spanish report about forest fires in the south of the island reaching La Orotava’s municipality boundary, which lies above the southern coast, a long, long way from the houses of the northern town.

Literary translators

Even with the tools available, being able to accurately translate at a basic level involves knowing the fundamentals of a language. Being able to convert one language seamlessly into a different one is another skill entirely. Literary translators are in the Champion’s League of translating. Think of Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy, or Carlos Ruiz Zafón’s wonderful The Shadow of the Wind. Reading them, I never once had a sense they were originally written in another language. The latter is particularly interesting because Spanish writing can have a tendency to veer towards the flowery side. Mind you, Zafón was Catalan, so maybe he didn’t exhibit the same general traits as his Castilian cousins.

Different writing styles

When we started out travel writing on Tenerife, we spent time in libraries in small towns poring through Spanish books looking for local snippets we’d never find in any English language articles. We collected reams of reading material from every municipality we visited. One thing was constant about the information within, there could be pages and pages of adjectives, similes, and metaphors to wade through to find factual info that was actually useful. I was reminded of this recently after a visit to Madeira. Following the trip, I researched what other writers had to say about the island, including an article by a Portuguese travel writer. His praise was poetic, lyrical, evocative to read. But ultimately it was an overdose of hyperbole. By the end, I knew the writer was smitten by Madeira, but of Madeira itself there was little information. Translating into a format that was more palatable for an English-speaking audience would require some serious chopping with the pruning shears.

Translating, really good translating, doesn’t just involve interpreting words, it involves interpreting meaning. In the case of novels that means capturing the soul of a book in an entirely different language. To be able to achieve that is simply a form of alchemy.

Yet, who knows the names of the translators responsible for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo or The Shadow of the Wind? Good literary translators are unsung heroes.